This article is Part 2 of the Rowing Injury Prevention Series, brought to you by Rowperfect UK. In Part 1, Blake Gourley wrote about general injury prevention tips. Next, Joe Deleo will discuss low back pain before Will returns to break down Snapping Hip Syndrome. These articles will take us right up to February 14th when the three of us will be featured on “RowingChat” right here on Rowperfect. These resources are presented to help you learn the specifics of strength training for rowing to improve performance and enjoy a healthier career. We hope that these will help you avoid making the same mistakes we have, and prevent you from having to re-invent the wheel. In the meantime, you can find us at our websites below.

Will Ruth: www.RowingStronger.com

Joe Deleo: www.leotraining.io

Blake Gourley: www.rowingstrength.com

The rib stress fracture is a rowing injury that plagues up to 24% of rowers and is to blame for the most time lost from on-water training and competition [13]. Because bone injuries can only be healed by time, prevention, not treatment, is everything for this injury. In 2007, the Journal of Sports Medicine claimed that, “the pathology and prevention of rib stress fractures will be one of the most useful areas of research in rowing training.” It’s been nine years and we’ve gone through two generations of rowers since then, and where are we on that? Dr. Anders Vinther has done extensive research on this topic and I agree with much of what he says regarding the merits of dynamic ergometers and the detrimental effects of upper body-heavy rowing technique. While his explanations of rowing training and bone healing with regard to stress fractures is very thorough, he makes only passing mention to the role of strength training in preventing this injury. US Rowing’s article by Boathouse Doc provides some great tips for training around the injury, but gives similarly brief treatment to strength training.

It’s time for rowing to break into the 21st century and get current with injury prevention.

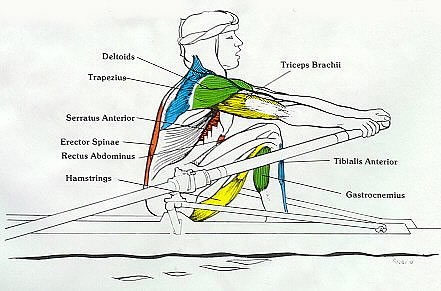

Let’s look at what muscular imbalances could cause this injury and try to address the real root of the injury. I have said numerous times that the #1 reason to strength train is prevention of injury, with performance improvement a distant second. Rowing is a highly asymmetrical sport, sweeping more so than sculling, and rowers who only row and do not strength train will develop structural imbalances. Strength training is the only way to isolate and train specific muscles that are under-developed by rowing.

While nearly all researchers and coaches who have tackled this issue have identified the serratus anterior as having some role in the injury, and many mention the role of strength training in injury prevention, I have yet to see anyone explain a muscle-focused plan for preventing the rib stress fracture.

Develop the Antagonists

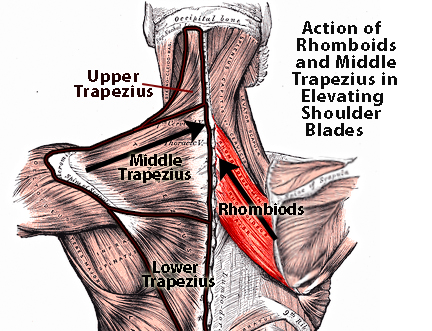

An antagonist, or opposite acting, muscle of the SA is the rhomboids. The rhomboids are the muscles in the middle of the back that retract the scapulae. Pinch your shoulder blades together without shrugging your shoulders up to feel the rhomboids work. While it may seem that the rhomboids get plenty of work from rowing, most rowers do not actually go through the full range of motion (ROM) of scapular retraction. The action at the finish is one of simply following through with the arms and latissimus dorsi, then popping the blade out of the water. Full scapular retraction at the finish does not occur, and thus, rhomboids are often underdeveloped in rowers. Rowers who do not include specific exercises for full ROM scapular retraction will not adequately develop their rhomboids to balance the SA’s strong protraction force.

A co-coach at Western confirmed that no one on our team has had a rib stress fracture in my career there, spanning the four years he had been a rower on the team. From the start, my programs have included specific work for the rhomboids and lower trapezius, among other exercises to develop the muscles of the upper torso. The team lifts 2-3 times a week throughout the year, every session includes at least one specific exercise for the mid-and-upper-back muscles, and overhead presses are a staple of the program. It’s estimated that this injury affects up to 24% of rowers and having zero on our team over four years is certainly a sign of something working, though as Blake mentioned in Part 1, never count out plain old good luck [5].

The Plan

If you currently exhibit any of the symptoms of a rib injury, see a medical professional as soon as possible and don’t try to train through the pain. It is possible that you’ve caught the injury early enough. Bone can only be healed with rest, so this could cost you a few weeks of training, but it’s better than losing a whole season and dealing with a lingering injury. Providing an exact rehabilitation plan is out of the scope of this article, as that needs to be left up to individual medical diagnosis and prescription.

Let’s talk prevention. Once you are rehabilitated and the bone is healed, or if you do not exhibit any of the symptoms, include some of the following preventative work in your training program. These exercises are not a comprehensive program for rowing training alone. For prevention of other rowing injuries and improved performance, your training should also include compound exercises for the upper and lower body as well as abdominal training for the rectus abdominis and abdominal external obliques. You can, however, add at least a few of these exercises into your program 2-3 times a week to improve muscle balance and cover your bases against the rib stress fracture.

-

Scapular retraction exercises

Strict horizontal pulling exercises with an emphasis on full range of motion, really pinching the shoulder blades together to work the rhomboids. Batwings, YWT raises, X-Band Rows, and other horizontal pulling exercises can be used. I typically program these with a pause of 1-2 seconds at peak contraction with a controlled eccentric (lowering) phase to really emphasize the finer postural muscles of the mid-back. Don’t go too heavy on these. Shoot for 2-3 sets of 10-15 paused reps at least once a week.

-

Scapular depression exercises

These exercises work the lower fibers of the trapezius muscle to counteract the upward rotation of the serratus anterior. A compound movement that emphasizes proper scapular function is the strict overhead press. Not all athletes will have the mobility to perform this exercise right away, so scale as necessary. Face pulls and YWT raises are great exercises for the lower trapezius. You can go heavier on overhead press, but keep the isolation exercises to 2-4 sets of 8-20 reps with very strict control.

-

Serratus anterior exercises

Start with the easiest isolation exercise, the lying protraction, then progress through the straight arm pulldown, band resisted protraction, wall pushup, and pushup plus. At the early stages of training, the purpose here is learning to activate the muscle and increasing bloodflow to the muscle with high reps. As athlete ability progresses to more compound exercises (overhead press in particular), SA exercises can just be used as an upper body warmup to maintain function or in a circuit of preventative exercises at the end of a session. 2-4 sets of 8-15 reps after the initial period of 2-3 sets of 10-20 reps.

-

Mobility

Thoracic spine mobility and serratus anterior self-massage will be critical for ongoing care of the muscular structures. The SA is usually a tender muscle, so start off easy on this with gentle massage and a soft foam roller.

-

Stop Testing Max Bench Pulls

I usually prefer to use positively worded advice, but there’s no beating around the bush here. Stop testing maximal bench pulls. We use a version of the bench pull in my programs, but we do it with dumbbells, refer to it as a “batwing,” and really emphasize the squeeze and retract at the top of the movement as it is done for reps of at least 10 per set. We do not test 1-rep maxes on the bench pull. The combination of the weight being directly supported by the rib cage and the resultant force of the arm and back muscles contracting to lift the weight put an incredible amount of pressure on the ribs. Why risk exposing the ribs to that amount of stress for a test exercise that has very little bearing on rowing ability?

READ MORE: Why I Hate the Bench Pull

Regardless of whether you use static or dynamic ergs, add some of these exercises into your strength training routine to cover your bases against a common injury in the sport. Remember, the #1 reason to strength train is injury prevention. Less time spent injured means more training time, more quality strokes, faster times, better performance, and a happier life beyond your athletic career.

References

Special thanks to Dr. Jane Thornton for email correspondence about this article and topic.

[1] Ebraheim, N. “Serratus Anterior Muscle Anatomy,” November 2013

[2] Hannafin, J. “Common Rowing Injuries,” FISA Medical Commission, July 2015

[3] Keogh, J. “Late Drive, Early Recovery,” 2013 Joy of Sculling Conference, February 2014

[4] Galilee-Belfer, A., and Guskiewicz, K. “Stress Fracture of the Eighth Rib in a Female Collegiate Rower: A Case Report,” Journal of Athletic Training, 35(4), 2000

[5] Mcdonnell, L., and Hume, P. “Rib stress fractures among rowers: definition, epidemiology, mechanisms, risk factors, and effectiveness of injury prevention strategies,” Journal of Sports Medicine, Nov. 2011

[6] Physiopedia, “Rib Stress Fractures in Rowers,” Physio-Pedia.com, retrieved 2016

[7] US Rowing Medical Commission, “Boathouse Doc: Rib Stress Fracture,” US Rowing

[8] Vinther, A. “The Dynamics of Rib Pain,” World Rowing, November 2015

[9] Vinther, A. “Rib Stress Fractures,” Presentation at British Rowing SSM Conference, December 2015

[10] Vinther, A. Presentation Slides for World Rowing Coaches Conference, 2010

[11] Vinther, A. “Rib Stress Fractures in Elite Rowers,” Lund University, 2008

[12] Vinter, A., and Thornton, J., “Management of Rib Pain in Rowers,” British Journal of Sports Medicine, April 2015

[13] Warden, S., and Crossley, K. “Aetiology of rib stress fractures in rowers,” Sports Medicine, 32 (13), February 2002.

5 responses

From the above I understand that a cause of rib stress fracture is the forceful extension of the arms for a long reach at the catch. This involves the use of the serratus anterior muscle attached to the ribs. What if we could achieve a similar reach using other forces?

In approaching the catch we have MOMENTUM in the form of moving blades, or erg bungie.

So! Approach the catch with the arms comfortably relaxed and about 10′ bent at the elbow. As your body stops against your knees, LET THAT MOMENTUM PULL YOUR ARMS STRAIGHT. Square the blade as this happens ( not before), and at full extension drop the spoon into the water. The arms immediately rebound and rebend to ‘catch’ the water or the chain. Your body reverses direction smoothly and work begins.

The serratus anterior did not do the arm extension. Happy ribs!

Using a stroke rate of 25+, with 1:1 in:out ratio will help this type of stroke.

You might also rotate your torso above the hips to achieve layback at the catch. Your upper body weight will then reduce rather than add to the load on your lower back during the work. Isn’t it natural to lean back when pulling something? So why are rowers coached to lean forward?

This technique is part of my ‘RHECON’ style. Visit if you like.

Have fun.

Breathing. The Serratus anterior also works to flex the ribs for breathing – DEEP breathing! By taking TWO BREATHS PER STROKE – out at catch and release – you will reduce this rib breathing effort. The cheapest, and biggest breathing volume – about 60% – uses the diaphragm.

Have fun.